Bloomberg is currently featuring the Austrian data privacy activist Max Schrems – and he takes apart the EU-US Privacy Shield, the successor to the Safe Harbor arrangement. The new agreement was cobbled together hastily, the product of pressure from the United States and the IT industry, complains Schrems – “and not of rational or reasonable considerations”. The 28-year-old considers it highly likely according to Bloomberg that the Privacy Shield, which came into force on August 1, will once again be stopped by the courts – leading to renewed legal uncertainty for globally active companies. For those who are not familiar with Max Schrems: the Viennese law student deserves to be taken seriously. With his class action lawsuit against Facebook he managed to convince the highest European court of law that Safe Harbor needed to be declared invalid. “He’s as big of a disrupter as Snowden,” attests Robert Bond, an experienced data privacy lawyer at Charles Russell Speechlys in London. Schrems’ lawsuit has had far-reaching impact on business.

The bone of contention in Safe Harbor was that data concerning European citizens was being transferred to the US and processed there by American internet companies – every Google search, every single “like” on Facebook and every single e-commerce order provided another little bit of big data, allowing the internet giants to refine their products, target their marketing more precisely and consequently boost their profits and market capitalization. The EU Court of Justice European found that the 16 year old Safe Harbor agreement did not protect the data of EU citizens sufficiently. While negotiators were still working flat out to finalize Privacy Shield, companies were compelled to conclude new private contracts to allow the legal transfer of data to business partners and affiliates across the Atlantic – at substantially higher cost and greater effort than having a single standard. The EU-US Privacy Shield should allay European data privacy concerns in the main – for instance, the agreement contains guarantees that data will not be gathered by US secret agencies without justification, and granting users the right to legal recourse should they suspect that their data is being misused. As Privacy Shield is also being contested in the courts, some enterprises would prefer to wait and see how the situation develops. Facebook, for example, has professed that it would first like to evaluate the text more closely. Microsoft, by contrast, yesterday announced that it would be complying with Privacy Shield.

“We have a right to privacy in the constitution”

Max Schrems was actually only alerted to the data privacy issues by US internet companies themselves, while studying abroad for a semester at Santa Clara University in the heart of Silicon Valley back in 2011. Attorneys from local technology companies, including Facebook, gave seminar lectures which showed a lack of recognition or outright disregard for European data privacy provisions. “They didn’t know a European was in the room,” remembers Schrems, who considers the right to data privacy to be as integral to the EU constitution as freedom of speech is in the US. Critics accuse Schrems and other data privacy activists of seeking unrealistic solutions. Privacy Shield strikes a better balance and provides Europeans with protective mechanisms that were previously lacking, according to Eduardo Ustaran, a London-based attorney specializing in privacy at Hogan Lovells International LLP. “Policymakers need to be ambitious and realistic in equal measure,” he said.

Up next: An NGO?

Max Schrems nevertheless believes that US technology companies will have to break the habit of expecting that what they have created in the US can simply be rolled out seamlessly and globally across borders. That’s why he may one day consider setting up an NGO which investigates and sues companies for violating data privacy. But first the young man from Vienna would like to complete his recently neglected PhD dissertation. “I’m basically working from home without any infrastructure and we still got a huge case done,” he says. “If you put that in a professional setting, you could possibly get a lot done.”

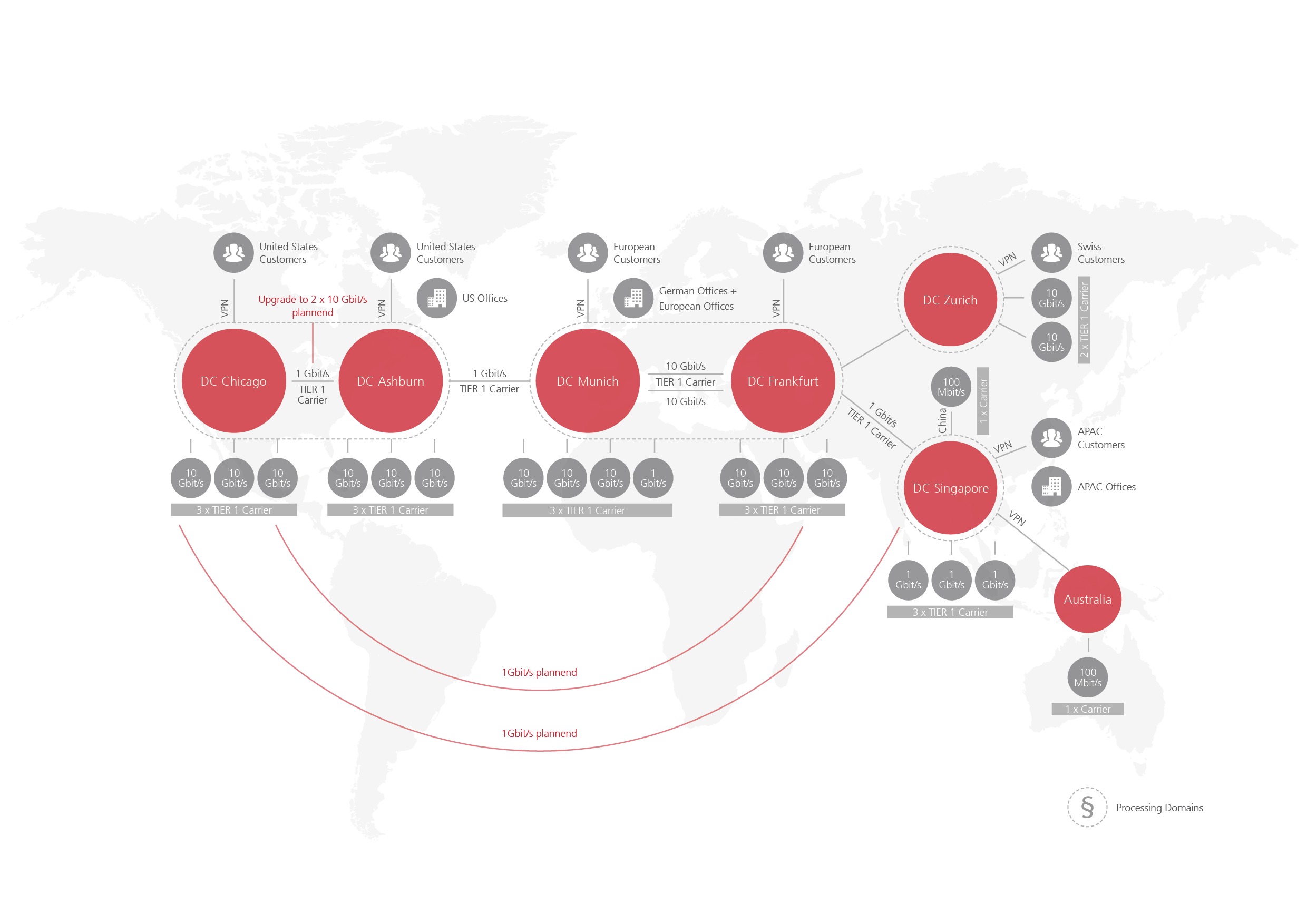

Retarus, incidentally, processes its customers’ data exclusively in its own, globally available data centers according to the requirements and data privacy regulations that apply locally to each specific customer. Individually auditable and certified, for instance, according to the data privacy laws, EU Directive 95/46/EC, ISAE 3402, HIPAA as well as PCI-DSS. You can find out more about data privacy and confidentiality in our Code of Conduct.